In the picture down below is Stonehenge, one of the most famous architectural monuments in the world!

It's hard to find anyone who hasn't heard of Stonehenge, yet nobody can say for sure what was the original purpose pursued by the ancient people who built it. In fact, the scientists would be grateful for any text or graphical description from the builders of this monument.

When it comes to “Stonehenges” in a codebase, it can be a great architectural solution that we use every day, building a whole system on top of it without really understanding why we or previous developers built it as they did. Perhaps, they had their reasons, but these are now completely irrelevant. We can't be sure.

However, a lack of understanding regarding the original reason behind implementing a specific element can lead to an occasional increase of complexity.

The importance of documentation

While many developers truly enjoy making and working with projects that have good documentation, they still tend to feel reluctant to write it. This paradox of a situation exists despite us, developers, understanding the importance of documentation. Still, the difficulty of writing and supporting a detailed description of the code does bear its burden. But is there a way to make it easier? I think there is! Let me show you it in this article!

Main problems of documentation writing

The main problem and, perhaps, the root of the rest of the problems is the separation of code and documentation. When we write our code and documentation in different systems (e.g. GitHub and Confluence), we have two different versioning systems for code and documentation. But what does this mean? Well, it can lead to the growth of project support complexity. For instance, every single change in a source code should be manually synchronized with documentation, while every single change in the documentation is to be connected to the source code.

This complexity often stops people from writing documentation at all, they may ask, "Why should we spend our time trying to write documentation for a project in development status?", adding, "We'll write the documentation when we get the completed product". This is possible, but, unfortunately, in real life, a "completed" project is a dead project. All live projects are in continuous development status. Thus, the only way to have good documentation is to write it in parallel with development, making this process as easy as possible with minimal overhead.

Take for example this, at different times and in different places, developers tried to solve this. For instance, Racket language has its own way to keep source code and documentation as close as possible by using Scribble, which allows us to integrate Racket code, including evaluating it inside the documentation:

#lang scribble/manual

@(require (for-label racket))

@title{My Library}

An example of the Racket code:

@racketblock[

(define (nobody-understands-me what)

(list "When I think of all the"

what

"I've tried so hard to explain!"))

(nobody-understands-me "glorble snop")

]In another example, if you're an Emacs enthusiast, you can use the awesome tool/language called Org Mode, which allows one to write complex documents, evaluate source code of different programming languages, and use the Literate Programming paradigm to keep all your source code within the documentation. Here's an example from its home page.

#+title: Example Org File

#+author: TEC

#+date: 2020-10-27

* Revamp orgmode.org website

The /beauty/ of org *must* be shared.

[[https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bd/Share_Icon.svg]]

** DONE Make screenshots

CLOSED: [2020-09-03 Thu 18:24]

** DONE Restyle Site CSS

Go through [[file:style.scss][stylesheet]]

** TODO Check CSS on main pages

* Learn Org

Org makes easy things trivial and complex things practical.

You don't need to learn Org before using Org: read the quickstart

page and you should be good to go. If you need more, Org will be

here for you as well: dive into the manual and join the community!

** Feedback

#+include: "other/feedback.org*manual" :only-contents t

* Check CSS minification ratios

#+begin_src python

from pathlib import Path

cssRatios = []

for css_min in Path("resources/style").glob("*.min.css"):

css = css_min.with_suffix('').with_suffix('.css')

cssRatios.append([css.name,

"{:.0f}% minified ({:4.1f} KiB)".format( 100 *

css_min.stat().st_size / css.stat().st_size,

css_min.stat().st_size / 1000)])

return cssRatios

#+end_src

#+RESULTS:

| index.css | 76% minified ( 1.4 KiB) |

| org-demo.css | 77% minified ( 2.8 KiB) |

| errors.css | 74% minified ( 4.9 KiB) |

| org.css | 75% minified (10.7 KiB) |Org Mode is a great solution if your team is familiar with Org Mode and Emacs. Even Github supports Org Mode, and you can use *.org files instead of *.md ones.

On the other hand, another problem arising from the separation of code and documentation is the weak cohesion between code and documentation parts. For example, we can describe a feature in our system, but every single part of the description is about different parts in our source files. This issue leads us to an inability to update certain parts of documentation after changing files connected to the source code or editing specific parts of those source files. Vice versa, while reading documentation, it's difficult to quickly find related source code for a certain paragraph of documentation. Without solving this issue, the complexity of documentation support will grow increasingly with the growth of project size.

But you may disagree and say, "That’s not true.Our API documentation doesn't have problems like that!" and you'll be right! You don't have such problems with API documentation or your Storybook documentation because it's generated from source code or with huge involvement of your source code in it. It has strong cohesion with source code and uses the same version control system as your source code. The only way to make writing project documentation easier, is to use the same set of tools as for code writing.

You can still solve this issue with tools like Scribble or Org Mode, but you'll need to combine different parts of documentation manually, which can be hard in big projects.

Documentation as code

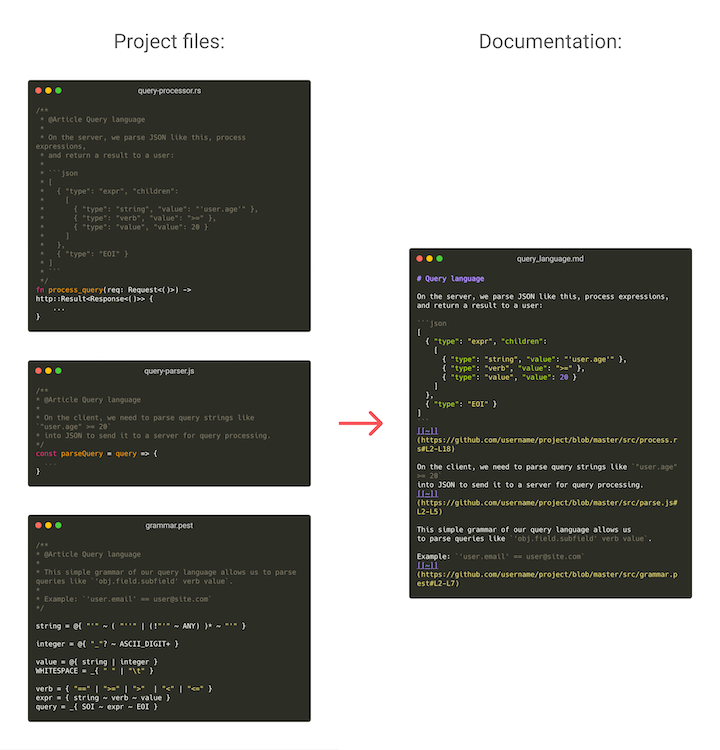

Keeping documentation and code together allows to achieve better control of changes and to make support of documentation easier. But without proper tools, it can be awkward to work with documentation for anybody other than the developers. For example, we can use markdown files for writing documentation, but if we place them near related source files, it will be difficult for managers, analysts, QAs, and designers to find something in this documentation. On the other hand, if we place them into a separate directory with its structure, we will not solve the issue with weak cohesion. In addition, with markdown files, we can't automatically create references from *.md files to particular parts of a source file, or we can't automatically combine all *.md files about the whole feature but written in the perspective of different source files. Let's look at the following example:

.

└── src

├── api

│ ├── auth.js

│ ├── news.js

│ └── offers.js

├── components

│ ├── auth.js

│ ├── header.js

│ ├── news.js

│ └── offers.js

├── index.js

└── reducers

├── auth.js

├── news.js

└── offers.jsThe example shows a simple project. Let's imagine we want to write documentation for our auth feature. The whole feature is implemented in three different files, but by "auth's implementation", all source files, not only api/auth.js or components/auth.js. So, to achieve strong cohesion between code and documentation, we should somehow place different parts of an article about authentication in different files and generate a single article from these parts.

If we do that, and even better, we add links to source code from a generated article, we can solve both problems with weak cohesion and using different versioning tools. But it'll still be a little awkward to use because good documentation should allow you to search through it and edit it.

The solution

I tried finding something which could solve all of these problems, but unfortunately, I hadn't found it. So I wrote my own tool called Fundoc to achieve all described goals and even more. The tool can:

- Keep documentation and source code as close as possible.

- Use the same version control system for documentation as for code.

- Be language agnostic.

- Collect all documentation from different repositories in one particular place.

- Allow non-programmers to read and write documentation.

So what can Fundoc do? It can generate documentation in two formats: raw markdown files (maybe later I'll add Org Mode support) and mdBook. The main idea behind this tool is to be as straightforward and uncomplicated to use as possible while providing all of the required functionality like search through documentation, documentation editing without the necessity to know the structure of a project, using one version control system, and so on.

But what do I use to keep the simplicity of a tool and the possibility to work with it for non-programmers? I use Github, that's it. Of course, in the future, it's possible to extend support of different services like GitLab, Bitbucket, or something like that. Let me explain how it works. Developers write documentation in source files or in markdown files marking every single documentation part with a simple marker that describes a result article title such as:

// src/api/auth.js

/**

* @Article Authentication

*

* To get authenticated, you should use the `login` function, which returns auth-token to pass it with API requests that require authentication.

*/

const login = (username, password) => {

// some code here

}

/**

* @Article Authentication

*

* To log out, use the `logout` method. It will invalidate the auth-token and delete it from cookies.

*/

const logout = () => {

// some code here

}And some description for a UI-part:

// src/components/header.js

const Header = props => {

const { isUserAuthorized } = props

/**

* @Article Authentication

*

* Only authorized users can see their balance in the header

*/

return (

<div>

...

{isUserAuthorized && <UserBalance />}

...

</div>

)

}This rather simple example will be compiled into one markdown file:

# Authentication

To get authenticated, you should use the `login` function, which returns auth-token to pass it with API requests which require authentication. [[~]](https://github.com/username/repository/blob/master/src/api/auth.js#L3-L7)

To log out, use the `logout` method. It will invalidate the auth-token and delete it from cookies. [[~]](https://github.com/username/repository/blob/master/src/api/auth.js#L12-L16)

Only authorized users can see their balance in the header. [[~]](https://github.com/username/repository/blob/master/src/components/header.js#L6-L10)To see more realistic documentation examples you can check out documentation of Fundoc itself or another project that used Fundoc.

In the compiled markdown file, you can see references to the particular parts of the source code. It allows you to find the exact source of every single part of the documentation. It can be useful for non-programmers if they want to edit documentation. If you believe they should still work with git to push their changes, they actually should not. Here's the example of editing documentation in the repository of Fundoc:

So on the gif, we can see that the only thing we need to edit our documentation is GitHub itself. Yes, it still requires an understanding of what GitHub is and the fundamental terms like "commit" and "branch". As practice shows, QAs, managers, designers, and analysts can handle it without any problems. At the same time, this way of working with documentation doesn't require knowing the file structure of a project from non-developers. It's definitely much easier than working with CLI-tools and dramatically easier than trying to synchronize Confluence and source code.

At the end of the article, I wanted to remind you that Fundoc now is in the beta state, and some APIs can change in the future. Otherwise, it already solves many problems and is used in different projects, so you can try to use it as well. If you have any questions or suggestions, feel free to send me them via Github issues or PRs. I'll be glad to make it better with your help!